Otto Frank File Found at YIVO

—Otto Frank File Found in YIVO Institute for Jewish Research’s Archives

—Details Difficulties Faced by Jewish Refugees Seeking to Flee Europe for the U.S. and Cuba

(NEW YORK, February 14, 2007) – Ever since the first publication of her diary in 1947, Anne Frank has been a very human symbol of the inhumanity of the Holocaust. The story of her family’s two years in hiding in an Amsterdam attic is known the world over. But what hasn’t been known is how desperately her father, Otto, tried to get his family out of the Nazi-occupied Netherlands – an effort that is detailed in a file of nearly 80 pages of original documents recently discovered in the archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research.

The bulk of the file, which consists of personal correspondence and official records, spans dates from April 30, 1941, almost a year after Germany invaded the Netherlands, to December 11, 1941, the day Germany declared war on the United States. A month later, the first Jews from Amsterdam were sent to Nazi work camps, and six months after that, the Franks went into hiding. The final documents pick up in June 1945, when Julius Hollander, the brother of Otto’s wife, Edith, sought information about the family’s whereabouts, and end in early 1946, when he was able to contact Otto, the sole survivor, who had made his way back to Amsterdam after being liberated from Auschwitz in January 1945.

The discovery of the Otto Frank file was fortuitous, since it was not known to be among the millions of documents housed at YIVO, one of five partner organizations that comprise the Center for Jewish History in New York City.

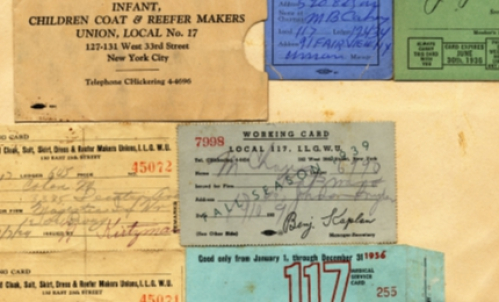

“The documents appear to have come from the files of the National Refugee Service, which, along with other organizations, merged into HIAS (originally the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) in the 1950s,” stated Dr. Carl J. Rheins, executive director of YIVO. “Over the years, HIAS has turned over thousands of records to YIVO, and the Otto Frank file was transferred with tens of thousands of other case files that filled some 350 four-drawer filing cabinets that HIAS turned over to YIVO in early 1974.

It was not until mid-2005 that a part-time volunteer at YIVO, Estelle Guzik, happened upon the file in a manila envelope and realized its significance. Ms. Guzik was checking the work of other volunteers who had been indexing files to make them accessible to researchers, scholars, and families searching the YIVO archives, and noticed that the date of birth had been omitted next to the name of Otto Frank on the file. Looking in the folder, she saw the daughters’ names and birth dates and realized that this was Anne Frank’s father. Ms. Guzik immediately reported her discovery to executives of YIVO, who “embargoed” the documents until potential copyright and privacy issues could be determined.

“With the release of the file, the plight of the Franks becomes even more poignant, since the family was unable to escape even with the help and support of a prominent American, Nathan Straus, Jr., son of the founder of Macy’s and head of the U.S. Housing Authority, a New Deal Agency,” said Dr. Rheins. A college friend of Otto Frank’s from Heidelberg University in Germany, Mr. Straus plays a major role in the drama that unfolds through the documents, from the very first letter Otto Frank wrote to Mr. Straus in April 1941 to ask for financial assistance in securing affidavits necessary for immigration to the United States.

In that letter, Otto Frank apologetically writes, “I would not ask if conditions here would not force me to do all I can in time to be able to avoid worse.” He goes on to stress that it was “for the sake of the children mainly that we have to care for. Our own fate is of less importance.” At the time of the letter, Jews in the Netherlands were facing increasing restrictions, having already been banned from owning radios and banned from the Civil Service, among other prohibitions; and an order had been issued requiring the registration of Jewish businesses. More directly urgent to Otto Frank was the fact that evidence (not included in the YIVO file) suggests he was being subjected to blackmail by a Dutch Nazi, and feared exposure and imprisonment as a racial and political opponent of the Nazi regime.

Nathan Straus, Jr., and his wife, Helen, according to the file, made several appeals on the Franks’ behalf to the Migration Department of the National Refugee Service, and contacted the State Department for information and assistance. Another key player in the endeavors to get the Frank family out of the Netherlands was Edith’s brother Julius Hollander, who had immigrated to the U.S. in 1939 along with another brother, Walter, and whose employer, Jacob Hiatt of Worcester, Massachusetts, generously supplied an immigration affidavit for Anne and Margot. Julius and Walter had enough savings to help secure immigration for their mother, Rosa Hollander, who was living with the Franks in Amsterdam, but could not provide funds for the entire family.

Unfortunately, their efforts were in vain, due to the vast numbers of refugees seeking safe haven, as well as drastic tightening of U.S. immigration policy – based partly on fears that some immigrants might be spies or saboteurs.

Noted Richard Breitman, Professor of History at American University, who studied YIVO’s file of documents, “In 1938, according to his own testimony, Otto Frank first applied at Rotterdam for immigration visas to the U.S. for himself and his family. By early 1939, the waiting list for an immigration visa to the U.S. contained more than 300,000 names. Under these circumstances, Otto Frank’s turn on the waiting list for American visas apparently did not come up. At that point, Germany had not yet invaded the Netherlands, and, feeling protected by his successful business in Amsterdam, Frank was not threatened enough to immediately try other opportunities abroad.

“However, opportunities to emigrate sometimes vanished very quickly,” Professor Breitman added. “By July 1941, American consulates in Germany and German-occupied countries were closed, so Otto Frank would have had to leave the Netherlands and reach Spain or Portugal before he could have any chance of getting U.S. visas for the family – meaning he would have to show an exit permit from the Netherlands and transit visas through the countries he would pass through. In addition, although Otto Frank did not realize it, under the new American visa regulations, he could not qualify for an American visa if he had any close relatives left in German territories. So the entire Frank family, including Edith’s mother, would have to get U.S. visas simultaneously, or none could qualify.”

When it became clear that new restrictions made coming directly to the U.S. impossible, the Strauses later offered to make required deposits for visas to Cuba for the Frank family. The subject of Cuba first arises in a September 8, 1941, letter from Otto Frank to Mr. Straus, in which he writes, “The only way to get to a neutral country are visas of others States such as Cuba … and many of my acquaintances got visas for Cuba.” Visas for Cuba were very expensive, since the Cuban government required, in addition to a visa fee, bonds totaling $2,500 per person, an amount that the Strauses were willing to deposit. On December 1, the Cuban government issued a single visa in the name of Otto Frank. Ten days later on December 11, Germany declared war on the United States and the Cuban visa was cancelled.

Had Otto Frank chosen to pursue emigration earlier than 1941, he might have faced an easier process. But, as David Engel, Greenberg Professor of Holocaust Studies at New York University, who also studied the YIVO file, stated, “Understanding the situation of Jews in the Netherlands under Nazi occupation, like understanding any aspect of the Holocaust, requires suspension of hindsight.”

Professor Engel pointed out that the Frank family, who were German, had already emigrated once, when they moved to the Netherlands in 1933 following the Nazi takeover of Germany. Otto Frank had established a successful business in Amsterdam, and knew that his two brothers-in-law were making only “ordinary workmen” wages in Massachusetts. What’s more, even when he began to investigate immigration to the United States in April 1941, Jews were still “pretty much able to go about their business as before,” Professor Engel said.

“During the first nine months following the Nazi occupation, little happened to suggest that Jews in Holland would be subjected to more than minor discrimination,” he added. “On the contrary, the situation of Dutch Jews (including refugees) appeared far more favorable than that of Jews in other Nazi-occupied countries.

“What’s more, the consensus among historians today is that when the Nazi regime came to power in January 1933, it had no clear idea how the so-called Jewish problem might best be solved. It was not until mid-1941 at the earliest that hopes for mass emigration were scrapped and concrete plans laid for total murder,” Professor Engel stated. “Neither Otto Frank nor anyone else could reasonably have predicted what would befall Jews in the Netherlands beginning in 1942.”

Otto Frank was able to survive the horrors of Auschwitz and died in Switzerland in 1980. Edith died of starvation at Auschwitz. Anne and Margot died of typhus within days of each other at Bergen-Belsen.

The original Otto Frank file will remain housed at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, and its contents will be made available on-site for research purposes. The YIVO Institute for Jewish Research is the world’s preeminent resource center for East European Jewish Studies and the American Jewish immigrant experience. It is a founding partner of the Center for Jewish History. An affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution, the Center’s mission is to preserve, research, and educate by fostering the creation and dissemination of knowledge and by making the historical and cultural record of the Jewish people readily accessible to scholars, students, and the broad public.

According to YIVO and Center for Jewish History Chairman Bruce Slovin, “The combined collections of the Center’s five partner organizations constitute an unparalleled wealth of more than half a million books and 100 million documents, forming the largest repository of Jewish archives outside of Israel. In fact, the massive archival holdings and a very large portion of the printed materials at the Center cannot be found in any other institution in the world. Thus the Center is not just a unique resource for researchers, scholars and families, it is a national and worldwide treasure-house of Jewish culture. And, it has earned the accolade as the ‘Library of Congress’ of the Jewish people in the Diaspora.”

The YIVO Archives hold more than 24 million documents, photographs, recordings, posters, films, videotapes, and items of ephemera, as well as thousands of handwritten, eyewitness accounts by Holocaust survivors and displaced persons. For further information, contact the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research 212-246-6080 or log on to www.yivo.org.

Read a timeline of key events related to YIVO’s Otto Frank File.

Read Prof. David Engel’s essay, “Background to the Situation of Jewish in the Netherlands under Nazi Occupation and of the Family of Otto Frank”

Read Prof. Richard Breitman’s essay, “Blocked by National Security Fears?: The Frank Family and Shifts in American Refugee Policy, 1938-41”