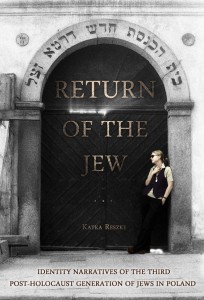

Return of the Jew: Interview with Katka Reszke

On June 24, 2013, in a program co-presented in partnership with the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, Katka Reszke appeared at YIVO to launch her new book, Return of the Jew: Identity Narratives of the Third Post-Holocaust Generation of Jews in Poland, with Dr. Sheila Skaff serving as moderator. The book is published in the U.S. by Academic Studies Press, and in Poland, as Powrót Żyda, published by Austeria.

Return of the Jew offers the first in-depth study of the so-called third post-Holocaust generation of Jews in Poland, those born in the late 1970s to early 1990s. It provides a revealing account of the experience of being or perhaps becoming Jewish in unique and compelling circumstances.

A new, "unexpected" generation of Jews made an appearance in Poland following the fall of the communist regime. Once home to the greatest Jewish community in the world and then site of the biggest tragedy in Jewish history, today Poland is experiencing what some have called a "renaissance of Jewish culture." Simultaneously, more and more Poles are discovering their Jewish roots and beginning to seek forms of Jewish affiliation. The Return of the Jew is multi-layered: there is the return to the Polish landscape of the Jew in discourse and imagery, but there is also the return of Jewish life.

Katka Reszke's book analyzes Jewish identity construction set against the backdrop of contemporary Poland with its difficult memory of the past and its new and complex Jewish culture. Can there be "authentic" Jewish life in Poland after decades of oppression?

Katka Reszke (Ph.D., Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel) is a researcher in Jewish history, culture, and identity. As a writer and documentary filmmaker, she specializes in human rights, social justice, minority and gender issues, as well as Polish-Jewish history and relations.

Yedies editor Roberta Newman sat down with her to discuss her book and her thoughts on Jews of the post-Holocaust generation in Poland today.

KR: I’m interested in how people create stories about their lives. In this context, the story of how they began to have a Jewish life. Not everyone in Poland in the third generation discovered Jewish roots. Some actually knew from the start. The question is what does it mean? Some people will say that they always knew, but they were never really raised Jewish or what we would understand as being raised Jewish. So everyone, whether they discovered it or not, really only embraced the idea of being Jewish in their teens, when they entered early adulthood. Basically, in terms of a time in history, we are talking about as early as the early 1990s and for some of the younger ones even at the beginning of this century. It’s a large generation because we don’t tend to have babies so soon in life. In this generation today, eighteen-year-olds and thirty-five-year-olds (like myself), are all part of the same generation, which only shows how problematic the term “generation” can be.

My approach was a social-anthropological one. The quotations are verbatim, so sometimes they’re messy, but I feel that it’s the right way to do it and I tried not to overinterpret the words. I tried to put this together into somewhat of a story. It’s always going to be a meta-story or even a meta-meta-story.

RN: Were all your interview subjects from this generation? Were any of them raised in Jewish homes? Did they grow up knowing that they were Jewish?

KR: Of the fifty people I interviewed, the best case would be someone who never went to church, but that still doesn’t make it a Jewish home, does it? Yes, everyone I interviewed was between eighteen and thirty-five-years-old at the time of the interviews, so they were young adults. And they were all people who had at least one Jewish grandparent. Some had a Jewish parent, some had a Jewish grandparent. And most of them knew it with some sense of certainty, and while others still can’t prove that they have Jewish roots. But that is the Polish story. Many of us are not able to prove our Jewish roots on paper.

RN: This book isn’t about you, but it is about you in some sense. Your own personal story is related.

KR: Yes, my personal story was a process of discovery of Jewish roots that took about eighteen years. And now I’m finished writing the book and my Jewish story of self- discovery continues and there are facts about my family’s Jewish roots that I came to know after the book was published, which is insane. The book, then, is about me in the sense that we’ve all experienced in one way or another becoming Jewish in a post-communist climate. And I mean becoming Jewish with Jewish roots, because it doesn’t include people who became Jewish who didn’t have Jewish roots. I could also have interviewed them but it’s beyond this research. That’s a different book.

RN: What led you to wonder about whether you might have Jews in your family tree?

KR: I’m asked this question a lot. Where did the hunch come from? A hunch is a hunch—it didn’t come from anywhere. I had no rationale for thinking that I was Jewish or that anyone in my family was. There was no conceivable reason that made me think this. And I have to be honest, I can’t remember the moment I decided I was Jewish. I know it must have been when I was around seventeen. As soon as I “decided” that I was Jewish, many people around me knew and they obviously asked me questions. I can’t figure it out. Obviously, there is this lovely romantic idea of the pintele yid, or the Jewish spark that supposedly dwells inside every Jew—but I am not big on magical thinking of this sort… And still sometimes this is the best explanation that you can come up with. The Polish Jewish story in this generation is par excellence a pintele yid kind of story.

RN: This brings me to a question: when you began to wonder if you were Jewish, why, actually, did you want to be Jewish? In Poland in this generation, it is no doubt a different story from what it would have been like forty or fifty years ago when people get these hunches that they were Jewish. Many more people seem to be willing to pursue it and not just continue to hide. What is it that makes it attractive today to come out and say I’m Jewish in Poland? What is it that made you, instead of being upset about it, interested in it when you were a teenager?

KR: I think the reason people in Poland want to discover sometimes not even provable Jewish roots and are likely to pursue a Jewish life and Jewish identity more than anywhere else is, I think, because it’s Poland. Because of its history and everything that happened in Poland. One single Jewish person emerging in a place like Poland has an entirely different meaning than a single Jewish person emerging in America. Of course it’s a question of statistics and numbers, obviously, but I think it’s more that. I think in some sense that there is this idea in all of us that we are personally responsible for Jewish survival. And I think in America it’s just less likely that people will feel this way because Jewish survival is quite secure here and it still isn’t in Poland and probably won’t be for quite some time.

I represent the optimistic branch in terms of thinking about a Jewish future in Poland. I think there is a Jewish future there and that there will be next generations of Jews. What they will be like is a whole other story. I think we’ve managed—and when I say “we,” I don’t mean our generation, I mean the two generations, the second and the third generations—I think that together we’ve managed to create some sort of basis for Jewish survival.

So I think there is a sense of mission. But many of us reject the notion of mission. I write about this in my book. Many people, when I ask them about mission they simply do not like the word. But when they respond to me they do talk about the sense of mission. There is a little bit of pathos in thinking of a sense of mission. Maybe they don’t like to identify with this romantic idea of responsibility for Jewish survival but they actually really do seem to feel it and they do talk about it. I can give you a quote from my book, which illustrates this:

“To be a Jew, to be a Jew from here, yes, from Warsaw, from this city where you walk on corpses, where you walk on human skulls, yes…This is no ordinary city, this is the New Jerusalem…It’s not an ordinary city; it’s a very important city, and a very important country…It is that feeling that this is your legacy, that you cannot forget, this it is important and that nobody will remember it for you. I have a part in the legacy of the Holocaust and my part in it is to try to understand. I ought to, I feel that I should, I feel this responsibility, this duty…to remember, to think about it, to understand, and to somehow transmit that memory. It is some kind of absurd reaffirmation of the covenant.”

This is heavy stuff coming from a twenty-something-year-old.

RN: I wonder what comes first for most people: discovering that you’re Jewish or knowledge of what took place in Poland. I don’t know too much about general Holocaust education in Poland, which, anyway, since this generation is so broad in age range wouldn’t have been the same for everyone in it. For instance, once you find out you might be Jewish do you already have the weight of the knowledge of Polish history, or do you first tend to find out that you’re Jewish and then start to explore that history?

KR: When I came of age in the early nineties there was a different curriculum in high schools than there is now. So I’m sure it’s a little different for an eighteen-year-old now than it was for me. I did have a sense of the Holocaust and I probably had as much knowledge about the Holocaust as I could as a teenager in Poland at the time, but I think that the first realization that came to me when I thought that I must be Jewish was that there were no Jews. And I think that some of that is still true for young people today. I think that’s why, in some way, you have to feel more important because we’re few. And obviously this will create a notion of elitism and you can turn it around badly but if we don’t remember, who’s going to do it for us? There is another quote from the same guy, where he says there’s one thing about young Jews in Poland: what do they really do? They’re not religious. What is so Jewish about them? If they identify as Jewish, what makes them Jewish? He says in a sarcastic way: “Young Jews in Poland drink beer and nobody else can do it for them.” And I think it’s a beautiful, existential conclusion. This is it. This is the core of our existence: to exist. That’s the idea: that we exist against the wildest expectations of everyone: Poles, Jews, and the world entire.

RN: That’s a heavy thing to grapple with when you’re a teenager. That brings me to one of things you talked about before, about realizing that you had a feeling that there was a future for Jews in Poland. One of the things you do talk about a lot in your book is that this is a creation of something new, rather than a recovery.

KR: Yes, this idea of a revival of Jewish culture in Poland is a little older even than our generation. It began in the late eighties and then we came along. And I think the fact that there was a “revival” of Jewish culture that began in Poland made it easier for us to come out as Jews because, obviously, you’re going to be more likely to come out as a Jew in a country that is suddenly positive about the idea of being Jewish.

RN: Is it suddenly cool to be Jewish?

KR: You know, that’s one of the things The New York Times asks all the time. Is it a trend? For the past twenty years people have been asking us if it is a trend and I think the answer to that is contained in the question. For the past twenty years. Trends do not tend to last over twenty years. And most people mean it as criticism when they ask this question.

RN: I mean it in a positive way! I mean it in the sense of it making you suddenly special and attractive if you’re Jewish.

KR: Most of the time when Poles find out I’m Jewish—and they find out within five minutes of conversation because it will come up. That’s what I do, that’s just what I am. So when they find out that I’m Jewish, most of the reactions will be “Wow, that’s so cool. Tell me more.” So, yes, there is that. I think the worst reaction I ever got was “Oh, I have nothing against the Jews,” and I love it - that’s the kind of antisemitism I encounter most often. I don’t encounter much worse than that. That’s not great, but it’s not dangerous. It doesn’t hit me in the face.

But I digress. This is not a revival of Jewish culture. I think what’s being created is an entirely new phenomenon that I call contemporary Polish Jewish culture, which is very specifically Polish, but that doesn’t take away from its authenticity. And I think the development we’ve seen with this phenomenon, is that over the past decade, Jews are now creating it together with Poles. Twenty years ago it was mostly in the hands of Poles. Over the past decade, if you go to the Jewish culture festival in Krakow, you will see, every year, more and more activities and events and workshops and whatnot that are created by Jews, or by Jews and Poles together for Jews and Poles alike. There are now more people coming from abroad to the festival because they’ve learned that it’s not like going to a reservation. That it actually has a quality of its own and it is a good quality. I think the Krakow festival is a perfect example of what should happen. How Jews and Poles now work together. And I always say that I know that some of the people in my generation owe their coming out to the aura of the “revival” of Jewish culture in Poland even though many of us wouldn’t want to admit it.

RN: Getting back to when I asked if it was cool being Jewish, I guess it made me wonder if this openness to Jews in Poland is part of Poland opening itself up to the world in a way that it couldn’t do before 1989. That it’s about a kind of Polish vision of the future of Poland and that Jews are just part of that.

KR: Definitely. Thousands of Poles have discovered that having lost the Jewish element in Polish culture was a very bad thing and there are efforts to retrieve not only the Jewish element, although I think that’s the biggest wave of this, there’s also interest in the Roma and Ukrainians and all kinds of minorities.

Poland had the reputation of being a very multicultural country between the two world wars and I think many Poles miss that reputation and would want to see it come back. I don’t think it’s possible that it will come back in the way that was before. There are so many things that happen that make people skeptical when I say this. There are many contradictory things that come out of Poland. The reason they come out and the reason you will hear about them is because we’re such a monitored community. The idea of there being a Jewish culture in Poland and of there being live Jews in Poland is suddenly very much on the radar around the world. Not just the Jewish world. Anything that happens in Poland with regard to Jews you will hear about tomorrow.

There’s something fascinating about that and I love it because I’m here [U.S.] and there. I spend on average, I think, between twenty to thirty percent of my time every year in Poland for the past few years. Eighty percent of what I do in Poland is something Jewish. I sort of go back to Jewish Poland. That’s what draws me to Poland: the Jewish life that I have there, that I’m part of, that I want to be part of. I always say that I feel most Jewish in Poland, and I’ve lived in Jerusalem and New York, which are probably the most Jewish places on the planet. And yet, it’s against the Polish landscape that my Jewishness manifests itself.

Interview transcribed by Melanie Halpern.

Read an excerpt from the book.

Buy the book.

Visit Katka Reszke’s website.