Shades of Red: The Yiddish Left-Wing Press in America

Shades of Red: The Yiddish Left-Wing Press in America, opened on May 6, 2012, in conjunction with YIVO’s international conference, Jews and the Left.

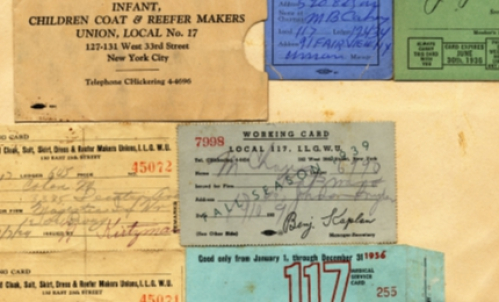

With the arrival of Yiddish speaking masses from Eastern Europe in the last decades of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Yiddish press evolved from a few small papers into a massive journalistic institution. Nearly all these Yiddish newspapers leaned to the left. Of the two mainstream dailies, Der Forverts (The Jewish Daily Forward, established in 1897), upheld socialism, the Jewish labor movement, and a mild version of anti-Zionism, while Der Tog (The Day, started in 1914), was non-partisan, liberal, and supported Zionism. Both would become very powerful voices in the Jewish immigrant community.

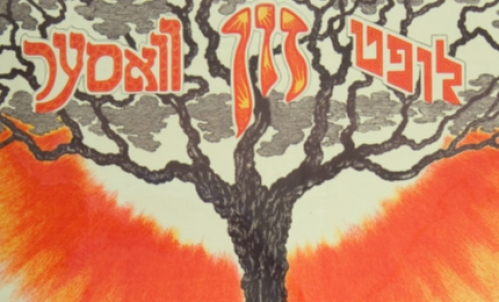

The move further leftward in the Yiddish press coincided with the arrival of new immigrants radicalized by the 1905 uprising in Russia and the pogroms that followed in its wake, as well as the Russian Revolution of 1917, which led directly to the founding of the New York Communist daily Di Morgn Freiheit in 1922 and its monthly magazine Der hammer (The Hammer). The paper attracted many young Yiddish writers “naturally inclined towards the left and seeking acceptance for fiction and verse more experimental than Abraham Cahan tolerated in the Forward,” as Irwing Howe wrote in World of our Fathers. Progressive writers and artists viewed Der Forverts with an utter contempt, regarding it both as a lowbrow rag, as well as a traitor to the left-wing cause. Though never rivaling the Der Forverts in terms of circulation, Di Freiheit had the most dedicated audience and was widely regarded as essential reading for those committed to the Soviet Union and the Communist ideology. It piously followed the Comintern’s diktats and remained loyal to the Kremlin when conflict arose between Jewish and the Communist party interests. With incendiary language and ferocious anti-Zionism and insulting cartoons enthusiastically contributed by such talented artists as William Gropper, Zuni Maud, and Yosel Cutler, the newspaper antagonized many in the Jewish community.

On the periphery of the mainstream there were other ideologically driven radical and sectarian magazines, proselytizing for their brand, such as ICOR, later Nailebn, which seized upon the scheme of settling Jews in the Soviet republic of Birobidzhan, and fought Zionism with messianic fervor as an expression of the bourgeois and chauvinist tendencies of the Jewish nationalism.

The Communist press adopted the view that Yiddish language and a total dedication to radical causes were the only acceptable expressions of Jewish national identity and used Yiddish in order to indoctrinate and disseminate Soviet propaganda. As Ruth Wisse writes in Drowning in the Red Sea: “Revolutionary Yiddishism turned out in practice to mean an adversarial relationship to America as well as to Zionism, a self-ghettoization in the name of a broader internationalism, and commitment to a culture of self-deception. Indeed, within fifteen years, no one was more eager to expunge this chapter from American Jewish history than those who had written it.” Thus the Yiddish press became not only the chronicler of Jewish history, but also the main forum for the Jewish ideological wars of the first half of the 20th century.